Emerge’s 2025 Project of the Year: The Deep‑Sea Machine That Snared an Ultra‑High‑Energy Ghost

Three and a half kilometers below the glittering surface of the Mediterranean, sunlight is only a memory. The water off the coast of Sicily is close to freezing, the pressure is thousands of times higher than at sea level, and anything not purpose‑built for this abyss would be crushed like a discarded soda can. Down here, in the cold and near‑perfect silence, humanity has built one of its strangest scientific instruments: a vast underwater observatory designed not to see light, but to listen for the faintest flashes of it.

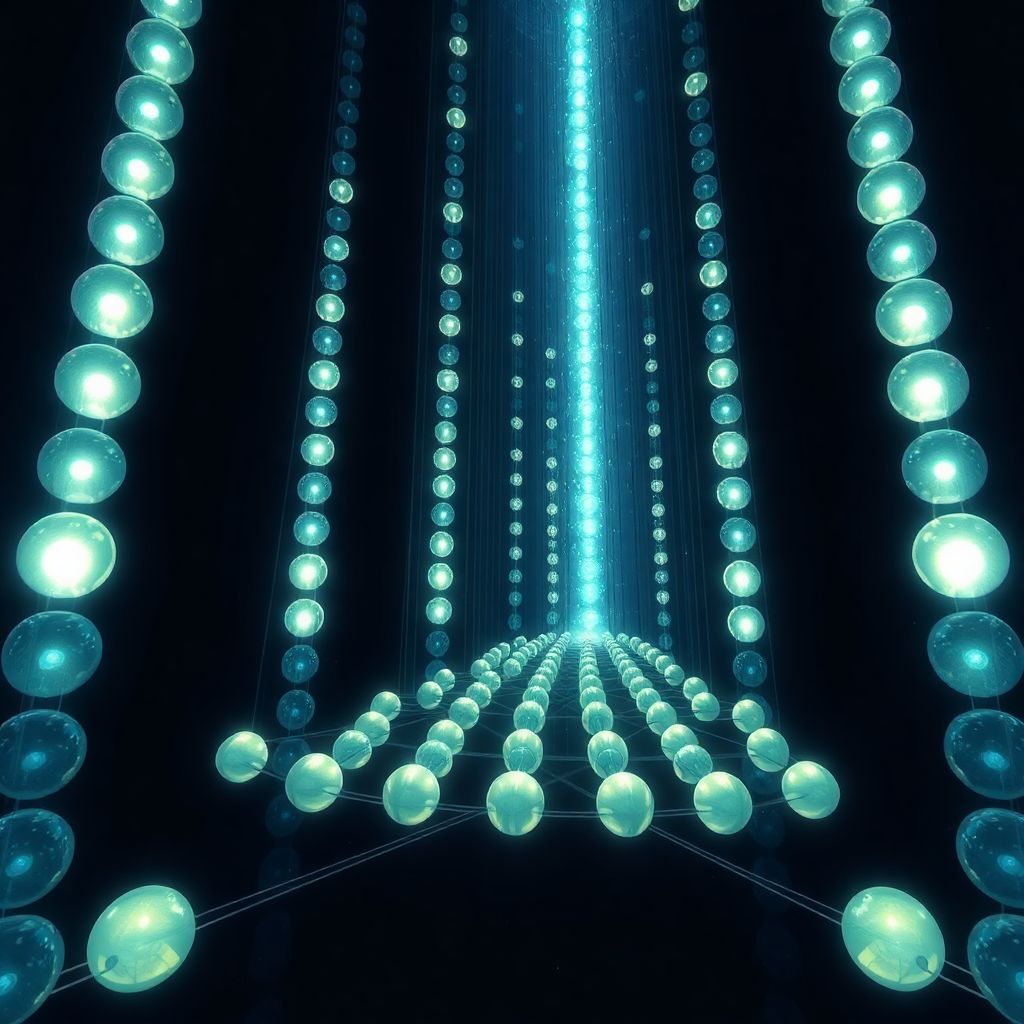

This is the Cubic Kilometre Neutrino Telescope Initiative—better known as KM3NeT—a sprawling forest of glass spheres and fiber‑optic cables anchored to the seafloor. It doesn’t look like any telescope you’ve seen. There are no mirrors, no domes, no giant dishes. Instead, there are vertical strings of delicate, basketball‑sized glass orbs, each one a pressure‑resistant capsule containing exquisitely sensitive light detectors. Together, they form what scientists sometimes call an “underwater cathedral,” a three‑dimensional lattice of sensors suspended in the black.

In 2025, that cathedral heard something extraordinary: a single subatomic particle, a neutrino, carrying more energy than any neutrino humans have ever recorded—around 220 peta‑electronvolts (PeV), roughly 220 million billion electronvolts. For comparison, the most powerful particle accelerators built by humans, like the Large Hadron Collider, reach energies of about 0.01 PeV. Whatever launched this neutrino did so with a violence far beyond anything we can reproduce on Earth.

The ghost particle paradox

Neutrinos are often described as “ghost particles,” not because they’re supernatural, but because they almost never interact with ordinary matter. Billions of them are streaming through your body right now—emitted by the Sun, nuclear reactors, distant explosions in space—and practically none of them will ever hit a single atom in you. They hardly notice that you, the Earth, or even entire stars exist.

That slipperiness is a blessing and a curse. Because neutrinos barely interact with matter, they can travel in perfect straight lines across the cosmos, unbothered by magnetic fields or intervening dust. They are pristine messengers from the most violent corners of the universe. But the same property that makes them perfect cosmic couriers makes them nearly impossible to catch.

To detect even a handful of high‑energy neutrinos, you need to monitor an enormous volume of transparent material—ice, water, or another medium—and wait patiently for the rare moment when a neutrino does collide with an atom. When that happens, it produces a charged particle that races through the medium faster than light can travel through that same material. That superluminal sprint creates a bluish flash known as Cherenkov radiation. KM3NeT’s glass spheres are designed to pick up these faint, nanosecond‑long blinks of blue.

Why build a telescope under the sea?

The Mediterranean is not just a scenic playground for yachts and beach holidays; it’s also a convenient laboratory. Deep‑sea water is extremely dark, remarkably clear, and shielded from much of the background noise that plagues detectors on the surface. The kilometers‑thick blanket of water overhead filters out most cosmic rays and other unwanted particles, giving the telescope a quieter environment in which to listen.

KM3NeT consists of multiple arrays of vertical detection lines, each line strung with dozens of optical modules—those glass spheres—spaced at regular intervals. Each module contains photomultiplier tubes that can detect even a handful of photons. When multiple modules pick up a flash, and the timing and pattern match the signature of a passing high‑energy particle, sophisticated software reconstructs the event: where it came from, how energetic it was, and which direction it was traveling.

The result is a telescope that doesn’t “see” the sky directly, but instead reads ghostly tracks of light passing through water, and from them reconstructs the invisible neutrinos that triggered them.

A tale of two telescopes: ice vs. sea

KM3NeT is part of a global push to understand the high‑energy universe through neutrinos. Its older cousin is the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, buried deep in Antarctic ice. IceCube was the first to convincingly demonstrate that high‑energy neutrinos could be traced back to cosmic accelerators like blazars—galaxies with supermassive black holes firing relativistic jets directly toward Earth.

But ice and water make for very different environments. Antarctic ice is stable and extremely clear, but it’s frozen in place forever. Once detectors are embedded, they cannot be retrieved or repaired. Sea water, by contrast, allows instruments to be deployed, serviced, and eventually upgraded. Moreover, the Mediterranean’s geography gives KM3NeT an excellent view of the Southern sky, including parts of the Milky Way that are less accessible to IceCube.

Together, these two enormous instruments—one carved into ancient ice, the other suspended in deep water—are complementary eyes on the neutrino sky. The detection of a 220 PeV neutrino by KM3NeT isn’t just a trophy event; it’s a crucial piece of a larger puzzle that these observatories are trying to solve: What are the engines that hurl such fantastically energetic particles across the cosmos?

The 220 PeV breakthrough

The neutrino that KM3NeT caught in 2025 was extraordinary not because it was visible to the naked eye—no one could have seen it—but because of what its properties revealed. The pattern of light detected by the underwater modules showed an ultra‑high‑energy event, far beyond what scientists had previously observed with such clarity in water.

Its energy, about 220 PeV, pushes it into an elite category of particles. These are often linked to the same astrophysical processes that produce ultra‑high‑energy cosmic rays, which are charged particles slamming into Earth’s atmosphere with unimaginable force. But while cosmic rays get scrambled by magnetic fields, losing memory of where they came from, neutrinos do not. A 220 PeV neutrino potentially points straight back to its birthplace.

Pinning down that origin is not trivial. Scientists must correlate the neutrino’s arrival time and direction with observations in other “messengers”: electromagnetic waves (from radio to gamma‑rays), gravitational waves, and even other neutrinos detected elsewhere. This approach—known as multi‑messenger astronomy—turns the cosmos into a coordinated orchestra of signals. The KM3NeT event, once fully analyzed and compared with data from space‑based and ground‑based observatories, could help identify or confirm a new class of cosmic engines: perhaps an active galactic nucleus, a tidal disruption event where a star is shredded by a black hole, or something even more exotic.

Engineering the impossible

Building a “telescope” at the bottom of the sea is a feat of engineering that borders on science fiction. Every component must survive crushing pressure, corrosive salt water, and the constant threat of mechanical failure in a place where sending a repair crew is extraordinarily expensive and dangerous.

The glass spheres that house the detectors are carefully designed to withstand pressures exceeding 300 times atmospheric pressure. The electronics inside must remain dry and operational for years, even decades. Cables running from the seafloor to shore carry power and data, and they must endure currents, biofouling, and geological activity.

Deploying the detector lines is its own choreography. Ships lower long, coiled strings of instruments to the seafloor, where they are then unfurled and tensioned into near‑vertical towers. Remotely operated vehicles inspect and sometimes manipulate the structures. Each step must be planned around weather, currents, and the ever‑present risk that something drops, tangles, or breaks.

And yet, the reward is a detector with a field of view spanning vast portions of the sky, operating continuously, tuned to the faint blue whispers of ghost particles.

Calibrating a cathedral of glass

Detecting Cherenkov flashes is only half the battle; translating those flashes into meaningful scientific events requires exquisite calibration. Every optical module must know its position to within a few centimeters. Underwater, that’s nontrivial: currents sway the lines, anchors can shift slightly, and the entire detector “breathes” with the ocean.

To track this subtle motion, KM3NeT uses acoustic positioning systems and tiltmeters to map the three‑dimensional configuration of the array in real time. Time synchronization is equally crucial. A neutrino event unfolds in billionths of a second, and each module’s timestamp must be accurate enough to reconstruct the trajectory of the resulting particle. This demands ultra‑precise clocks and sophisticated timing protocols pulsing through the network of cables.

When a candidate event appears, algorithms sift through mountains of data, separating true neutrino interactions from background noise: bioluminescent flashes from deep‑sea organisms, faint traces from passing muons created by cosmic rays in the atmosphere above, and random electronic glitches. The 220 PeV detection survived this gauntlet, emerging as a clean, rare, and scientifically priceless signal.

What ultra‑high‑energy neutrinos can tell us

Why does one solitary particle matter so much? Because at these energies, neutrinos probe regimes far beyond what particle accelerators can reach. They let physicists test models of how nature works at scales that would otherwise be completely inaccessible.

Ultra‑high‑energy neutrinos can:

– Reveal where and how cosmic rays are accelerated to such staggering energies.

– Constrain or support theories involving dark matter, exotic particles, or new interactions.

– Provide insights into the behavior of matter in the extreme environments around supermassive black holes and neutron stars.

– Help refine our understanding of how the universe evolved on the largest scales.

Each event is like a postcard sent from a violent corner of the cosmos, stamped with the conditions at its origin. But the message is encoded in the particle’s energy, direction, and arrival time. Detectors like KM3NeT are the decoding machines.

The dawn of a new astronomy

Neutrino astronomy is still young compared to traditional optical or radio astronomy, but it is rapidly maturing. The first era of neutrino physics, in the late 20th century, focused on neutrinos from the Sun and supernovae—low‑energy particles that helped solve puzzles about particle masses and oscillations. The current era is different. Now, the focus is on high‑ and ultra‑high‑energy neutrinos that act as signposts of the most extreme astrophysical processes.

The 220 PeV signal marks an important milestone in this shift. It shows that deep‑sea telescopes can not only compete with ice‑bound observatories but can push into regimes where new phenomena may emerge. This is especially important as other observatories, from gamma‑ray telescopes to gravitational wave detectors, expand their sensitivity. When a distant event—say, the merger of two neutron stars or the sudden flare of a supermassive black hole—lights up the sky, scientists increasingly expect to see a coordinated response across multiple messengers, including neutrinos.

In this vision of astronomy, the universe is no longer seen only through light, but through a chorus of signals: ripples in spacetime, charged particles, ghostly neutrinos. KM3NeT is one of the instruments that make this symphony audible.

Life and noise in the abyss

One of the surprising challenges for a deep‑sea neutrino detector is that the deep ocean is not as quiet as it seems. Bioluminescent organisms flash and shimmer, creating photons that can mimic the signals of low‑energy events. Microorganisms colonize surfaces, altering optical properties over time. Currents flex the towering lines of sensors, sometimes changing their orientation.

To separate cosmic signals from ocean life, scientists have had to become, almost accidentally, oceanographers and biologists. They monitor patterns of bioluminescence, seasonal changes in deep‑sea conditions, and the slow accumulation of life on the hardware. These background studies are essential to ensure that when a genuinely extraordinary particle like the 220 PeV neutrino arrives, its signature stands clearly above the natural chatter of the sea.

From prototype to planetary network

KM3NeT is not a single instrument but a growing network, with separate clusters designed for different energy ranges and scientific goals. One branch focuses on high‑energy astrophysical neutrinos, hunting for events like the 220 PeV signal. Another is tuned to lower energies, targeting neutrinos produced in the Earth’s atmosphere or in the core of our own galaxy.

In the coming years, additional strings of detectors will be deployed, expanding the telescope’s sensitivity and field of view. At the same time, plans are advancing for next‑generation neutrino observatories around the globe, from the Pacific to the Arctic. The long‑term vision is a planet‑scale network of detectors that can pinpoint neutrino origins with far greater precision and capture far more of these elusive messengers.

As the network grows, so does the chance of catching multiple ultra‑high‑energy neutrinos from the same source, or of seeing neutrinos in near‑real‑time from a cosmic explosion spotted in photons or gravitational waves. That would transform one‑off discoveries into systematic science.

Why this deep‑sea machine matters beyond physics

At first glance, a neutrino telescope buried in darkness seems remote from everyday life. But the technologies and methods developed for KM3NeT have wider implications. The pressure‑resistant glass, robust underwater connectors, and long‑lived electronics feed into broader advances in deep‑sea engineering, with potential benefits for communications, environmental monitoring, and resource management.

The data analysis and pattern‑recognition techniques pioneered for neutrino hunting are closely related to those used in other data‑intensive fields, from climate science to finance. The project’s requirement for ultra‑reliable distributed systems under harsh conditions echoes challenges faced by underwater internet cables, offshore energy infrastructure, and remote sensing.

Perhaps more importantly, projects like KM3NeT demonstrate a kind of scientific ambition that looks beyond immediate utility. They are bets that deep understanding of nature—right down to the rarest particles—will eventually reshape how we think, invent, and live.

A machine listening for whispers in the dark

In the end, the story of KM3NeT and its 220 PeV neutrino is about patience and audacity. Humanity sank a massive, intricate instrument into a part of the planet where no light from the Sun can reach, then asked it to wait, sometimes for months, for a single significant event. When that event finally arrived, it was over in less than a microsecond—a brief blue whisper in a cubic kilometer of black water.

From that whisper, physicists can reconstruct the violent story of a particle born in a distant, cataclysmic process, accelerated to absurd energies, and sent on a billion‑year journey across intergalactic space. It passed unhindered through galaxies, nebulae, perhaps entire planets, until it finally clipped an atom in the dark waters of the Mediterranean and announced its presence with a flash.

That improbable meeting—between a ghost particle from the depths of space and a machine built in the depths of the sea—is what makes KM3NeT Emerge’s 2025 Project of the Year. It is a reminder that some of our most profound connections to the universe happen far from where we can see, in places of crushing pressure and perfect darkness, where we’ve taught machines to listen for the faintest echoes of cosmic violence.